The stardust alien: from Hull to eternity

I stopped listening to David Bowie a year ago. My love for his music was undimmed but I had come to the conclusion that old tunes were crowding out the new – at least on my playlists. I decided that, for a while at least, I would embrace the contemporary. In fact, I gave up listening to anything recoded before 2010.

To fill my soundscape, I read reviews, sought the views of friends and experimented. The experience has reinvigorated my love of music. It has, however, led me to a paradoxical observation. It is possible, I discover, to immerse oneself in newly-recorded music while retaining a resolutely 1970s sensibility. I have loved Low Cut Connie – who owe more than a little to Villa Nellcôte era Rolling Stones. Natalie Prass has significant echoes of Dusty In Memphis and Taylor Locke has produced the album with which Fleetwood Mac should have followed up Rumours.

The Spitfires sound like The Jam’s first album. Courtney Barnett megamixes Jonathan Richman with Pulp. Royal Headache would not have been out of place on the Anarchy Tour. Straight lifts from disco, soul and new wave of that era can be found just as easily.

Perhaps that is quite normal – reinvention and rediscovery has always been at the heart of music. Despite this however, no one has ever created either sounds, or personas to rival David Bowie. You can find his influences, of course, but there isn’t an artist at any time since his vault to stardom who approaches his scope, ambition or otherworldliness.

I can’t proffer profound insights in to his trajectory from south east London to stardom. A couple of years ago, however, Woody Woodmansey, the Spiders from Mars’ drummer, shared his recollections of his early years with Bowie with an audience at the Latitude Festival.

I had long wondered about how this encounter took shape. The realty was a hundred times better than I had imagined.

The bones of the tale are well-known. By 1969, Bowie had skirted success for several years and was living semi-communally in Haddon Hall, a gothic pile in Beckenham, south-east London. He needed a band and through chain migration assembled Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Woodmansey, who knew each other from performing in the pubs and clubs of their native Hull.

I did not take notes at the event, so I am quoting from memory. Suffice to say, the trio of Yorkshiremen, who had given up manual trades only days before departing for the capital, found their billet at Haddon Hall mind-expanding.

“There were birds – girls that is – loads of them, and people who you could not tell what they were. There were lots of drugs and folk who just floated in and stayed for a while and then floated off again,” Woody recalled. “For quite a while, we couldn’t really believe our eyes”.

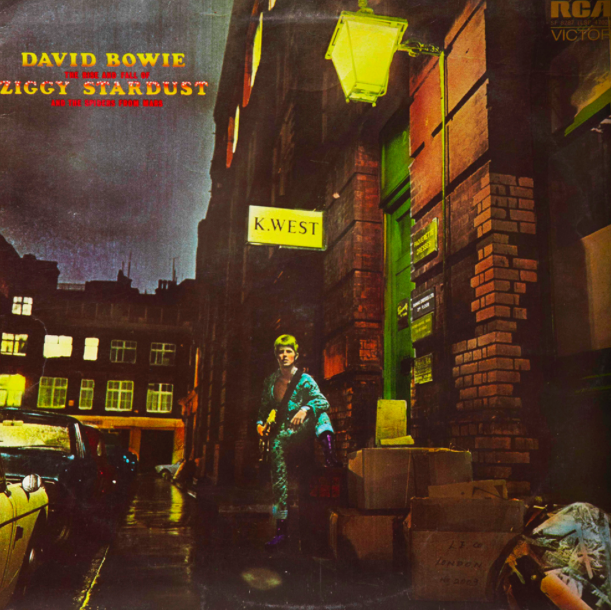

They were impressed with Bowie’s musical vision and the three exceptionally capable rockers were soon adding their own magic to the songs that would eventually appear on Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust. Bowie’s ideas about clothing, however, were rather harder to stomach.

“He took us all to Liberty (the department store) to show us all these pink satins that he thought we should wear”, Woody explained in his board Yorkshire brogue. “We had never seen ‘owt like it before. Eventually Mick cracked. ‘I’m not dressing up like some kind of pansy’ he exploded. ‘They have telly in Hull, you know, me mates and me mam might see us’.” With this, the guitarist stormed off, swearing to return immediately to the East Riding and its sartorial certainties.

Woody was deputised to save the day. “I chased him all the way to Kings Cross where he was actually on the train before I begged him to come back”, Woody said.

Thanks be that he did. Ronson’s intuitively liquid guitar licks, not to mention his full embrace of glam-rock gender bending, were a significant contributor to Bowie’s breakthrough moment on Top of the Pops in 1972. That he and Bowie are spoken of in the same breath as Jagger/Richards, Page/Plant shows just how important his contribution was to the Spiders’ success.

What can be drawn from any of this in this moment of Bowie’s demise?

Two things, perhaps. One that in the parthenon of popular music we will have a long wait before Bowie is rivalled in his capacity for reinvention, and defining the myriad musical styles he embraced. More importantly, though, however otherworldly he appeared, his artistry was ultimately rooted in the same prosaic, everyday considerations as the rest of us.

Bowie once said: “I’m not a prophet or a stone aged man, just a mortal with potential of a superman.” We might lack his transcendental powers of expression but, I think, the same is true of us all.