The living dead: my faith was renewed at a socialist pioneer’s graveside

Hollywood and horror writers have seen to it that graveyards evoke feelings of dread, fear and apprehension. At best they are where the grieving outpour their despair; at worst they are the scene of spines chilled, foul deeds and the rising dead.

Wandering around the monumental Victorian remembrances in Dundee’s Balgay cemetery, I came upon a tomb stone that turned my mind to a rather different narrative, a version of which can almost certainly be found in any municipal necropolis.

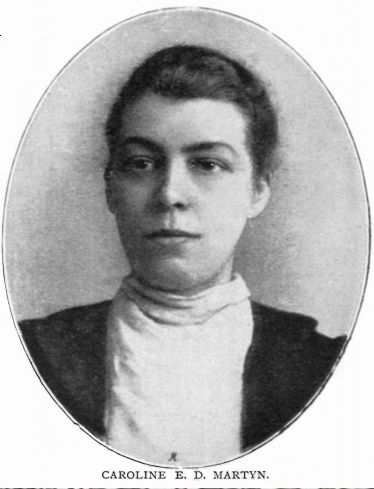

Close by the entrance, in the steep, wooded valley that was apparently frequented by smugglers and ne’er do wells as late as the mid 1800s, is a tall, broken column, fashioned from polished red Peterhead granite. The dais beneath reads: “A token of the esteem to the memory of Caroline E R Martyn. Born Lincolnshire 3 May 1867, died at Dundee 23 July 1896. A devoted worker in the cause of humanity”. Below that an inscription records that the monument was erected by: “Socialist comrades and Dundee Textile Workers Union”.

Its height, nine feet six inches, is on a scale with the surrounding industrialists’ and professionals’ resting places – suggesting that her’s was a death that caused widespread mourning. Many pitifully-paid jute-mill workers must have contributed to fund such a significant memorial.

Its height, nine feet six inches, is on a scale with the surrounding industrialists’ and professionals’ resting places – suggesting that her’s was a death that caused widespread mourning. Many pitifully-paid jute-mill workers must have contributed to fund such a significant memorial.

Carrie Martyn, as she was known in life, was, it transpires, a remarkable woman. She edited socialist newspapers, relentlessly organised the most badly treated industrial workers into unions, and most significantly, toured the country speaking to open-air meetings – some of them attracting audiences of thousands. She and Keir Hardy – with whom she served on the Independent Labour Party’s national executive – toured Britain preaching their cause. When she died, Hardy wrote that Martyn was: “the leading socialist of her day with a powerful intellect and a moral force that was unmatched”.

Forgotten for many years, Martyn’s memorial garnered fresh attention in 2009 when the inquiries of an amateur historian in England led the secretary of Dundee Trades Council, Chris Arnott, to search the city’s cemeteries for her grave. He came upon it, missing its column and entirely forgotten. Detective work on his part, a lucky find and support from today’s trades unionists have transformed the memorial. It stands erect, as intended, cleaned up and with fresh flowers and a picture of Martyn at its foot. An excellent account of her life has also been published.

Martyn’s is a story well worth celebrating – but it is surely not the only one at Balgay, or any other burial site? Whether or not you have faith in an afterlife, for the living, our most important relationship with the dead is how we remember them. In this world, the lives of the deceased obtain meaning by the inspiration they provide us, the lessons learned from their endeavours and the way in which celebrating their achievements spurs us anew to shape our own lives.

So forget the gothic window dressing, the bats and storytellers’ hokum about zombies and ghosts. Apply a lively mind to any graveyard and the real-life stories that have shaped its creation and you will find an abundance of living energy – sufficient to sustain and nourish you though a great many everyday travails.

Photograph © Tim Dawson