Face to faceless: going solo to thwart the eurocrats

To its detractors the European Union is a faceless, unresponsive monolith, remote from the citizenry and indifferent their needs. That an EU Commissioner might listen to an individual’s voice, much less change European policy on the basis a single voter’s argument is, perhaps, hard to imagine. But I know from experience that it can happen; and my encounter with a Commissioner was entirely accidental.

In the late 1980s, I was employed as the National Union of Students’ communications officer. My job was to write and edit publications on behalf of the elected student officers. In this role, I had produced a couple of articles and briefings about draft EU legislation that would have tightened up the rules in respect of who could drive a minibus. The critical proposal was that a professional Passenger Service Vehicle driving licence would be required before you could take to the wheel of a Transit-based van. My formal involvement in what became known as the Great Minibus Campaign, however, was peripheral.

NUS cared about minibuses because they provided the backbone for much student activity. Students unions at that time operated minibus fleets to enable self-organised groups of undergraduates to transport themselves to sporting fixtures, field trips and cultural visits. This was possible because a regular driving licence allowed you to drive a ’12-seater’. The proposed EU legislation was motivated by a desire to professionalise the operation of such vehicles, thereby making their operation safer. The effect of such a change, however, would be to bring to an end the vast majority of student sport and much else beside.

NUS’ had long been a campaigning body, but the Great Minibus Campaign was different. Recognising that stroppy students alone were unlikely to change minds in Brussels, NUS built ‘The Mobility Alliance’ a coming together of organisations whose work rested heavily on volunteer-driven minibuses. The Sunshine Variety Club, Lords Taverners, Barnardos and Help The Aged all came on board. With them they brought celebrity contacts beyond the wildest dreams of student politicians. I still have a picture of Sarah Adams, then vice president of NUS, Willie Rushton, and junior transport minister Peter Bottomley taking an enormous axe to a model minibus for a photo stunt.

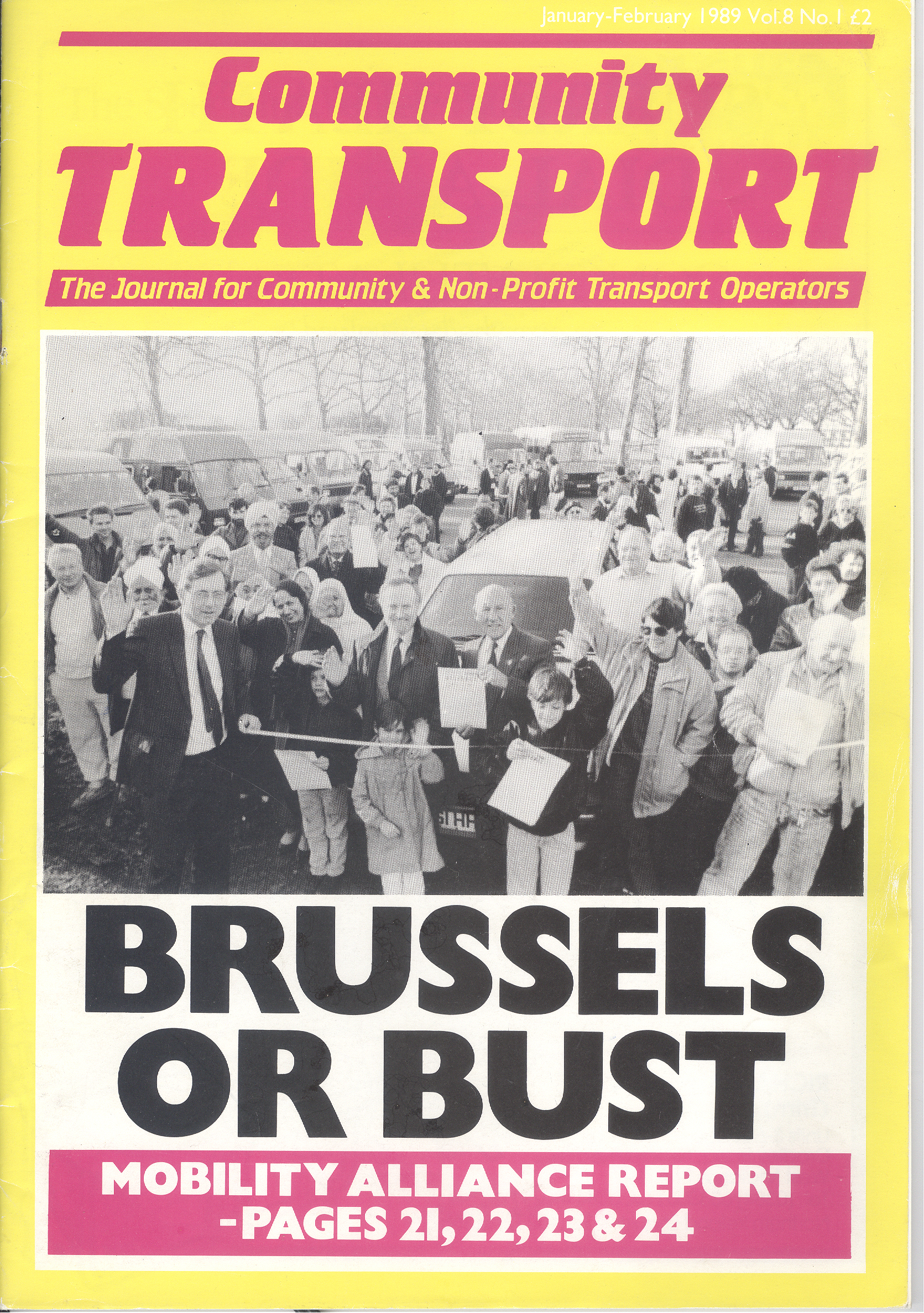

The culmination of the campaign was a minibus cavalcade to Brussels where transport Commissioner Karel Van Miert had agreed to meet with protesters. I had no role in this, until the morning that the caravan was due to depart London’s Battersea Park (12 December 1988). Doug Taylor, NUS’ general manager, phoned me to say that his photographer had let him down. Was there any chance that I could come to the launch and take some pictures, which could then be handed out to journalists in Brussels? I had taken photographs as a student journalist and undertaken the occasional professional commission, so I agreed. NUS’ president, Maeve Sherlock loaned me the NUS car, and I set off.

The crowd at the launch was fantastic – Sir Stirling Moss arrived riding a step-through moped, Peter Bottomley turned out again as did tv musician Richard Stilgoe. I took some shots, and the minibuses departed for the coast.

My plan was to have some 10 x 8s printed and then catch the convoy before it boarded the ferry to Belgium. The contact sheet took an hour, and happily one of my 32 exposures seemed to fit the bill. I ordered some prints and waited an agonising half hour.

London’s traffic was worse than I had bargained for and by the time I got to the Dover, my colleagues had already embarked. I drove to the dockside, and charming my way past several security points with a garbled story about a ‘mercy mission to help disabled children’. Eventually I pulled up right beside the boat, ran up the gangplank and started a frantic https://nexiumreviews.com search for the EU-bound party.

As I came upon them, however, two urgent hoots signaled that the boat had slipped its moorings and was now destined for foreign shores. The timely delivery of the photos, mercifully, rendered my boss indulgent. Why not add a ticket-less tag-a-long to the party?

We traversed Belgium uneventfully, and put up for the night the Jacques Brel youth hostel. With neither overnight bag nor change of clothes my jeans and jumper were never going to look very smart. Beside my colleagues’ Next suits, purchased specially for their Euro-encounter, I felt distinctly down-at-heel.

The morning plan was to drive to the Commission building, lobby and then return to London. I was to stay with the vans. It was soon clear, however, that we had miscalculated Brussels’ traffic and the scarcity of parking. As the appointment approached we were still circling the EU offices.

“Not to worry”, I said. “I will get out and forewarn the officials of your slight delay”. I jumped from the van and dashed in.

The Commission’s staff were unimpressed. “We can wait only a few minutes, but the Commissioner is very busy. Your colleagues must be on schedule or miss their meeting”. I looked to the door in desperation – there was no sign of them. Minutes ticked by. I pleaded with the officials to exercise some discretion. They were unrelenting, and the Next suits were nowhere to be seen.

Eventually, Van Miert’s aide put his foot down: “either speak to the Commissioner now, or he will leave the building and you will have missed your opportunity”. So looking desperately over my shoulder with every step, unwashed, unshaved and in yesterday’s clothes, I entered the great man’s office.

Apparently indifferent to my discomfort, Van Miert listened carefully. I scraped the recesses of my memory and painted a torrid picture of the unplanned consequences of his initiative: no holidays for disabled children, Scout camps cancelled and Britain’s undergraduates becoming fat and lazy for lack of sporting opportunities. With every faltering word, I prayed for the arrival of my colleagues with their practiced presentations.

Van Miert took careful notes, asked me a few questions and promised to consider my case.

By the time I exited his office, I was certain that my shakes were visible. It was not until I returned to the Commission’s vast lobby that I saw my friends. Bursting through the main doors just as the lift deposited me on the ground floor, they sprinted through the lobby like so many bulls storming Pamplona. They had all but passed me before my calls halted them. I might have made a better job of apologising for stealing their moment had I not been still in shock from my surprise encounter.

It was some time before they accepted that I had taken the only available course of action. Their disappointment was tempered significantly some months later when Van Miert announced that he had been persuaded by our case and redrafted his intended reform. No doubt it was the broader campaign, with its briefing documents and submissions that really turned the tables, but I like to imagine that my off-the-cuff persuasion played at least a modest part in our victory.

It was some time before they accepted that I had taken the only available course of action. Their disappointment was tempered significantly some months later when Van Miert announced that he had been persuaded by our case and redrafted his intended reform. No doubt it was the broader campaign, with its briefing documents and submissions that really turned the tables, but I like to imagine that my off-the-cuff persuasion played at least a modest part in our victory.

Happily, on the day, Brussels’ lobby correspondents showed no interest in our cause, consequently there were no takers for the photographs whose delivery had brought me Belgium. News that a stowaway had been the only one present at the big meeting would surely have opened our campaign to ridicule?

Upon our return, however, the estimable Community Transport magazine surprised me by using my image as their cover shot – the crowning glory to a story in which I had a pivotal, if hitherto unsung, role.